Psychology of a CrisisPsychology of a Crisis

2019 Update

CS 290397-E

2 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Explanations of figures for accessibility found in the Appendix: Accessible Explanation of Figures on page 16.

This chapter will introduce:

Four Ways People Process Information During a Crisis

Mental States in a Crisis

Behaviors in a Crisis

Negative Vicarious Rehearsal

Addressing Psychology in the CERC Rhythm

Crises, emergencies, and disasters happen. Disasters

are different from personal and family emergencies,

and not just because they are larger in scale. Disasters

that take a toll on human life are characterized by

change, high levels of uncertainty, and complexity.

1

In a crisis, affected people take in information,

process information, and act on information

differently than they would during non-crisis

times.

2,3

People or groups may exaggerate their

communication responses. They may revert to more

basic or instinctive fight-or-flight reasoning.

Effective communication during a crisis is not

an attempt at mass mental therapy, nor is it a magic

potion that fixes all problems. Nonetheless, to reduce

the psychological impact of a crisis, the public should

feel empowered to take actions that will reduce their

risk of harm.

This chapter will briefly describe how people

process information differently during a crisis, the

mental states and behaviors that tend to emerge in

crises, how psychological effects are different in each

phase of a crisis, and how to communicate to best

reach people during these changing states of mind.

3 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Four Ways People Process Information

during a Crisis

By understanding how people take in information during a crisis state, we can better plan to communicate

with them. During a crisis:

We simplify messages.

4

Under intense stress and possible information

overload, we tend to miss the nuances of health

and safety messages by doing the following:

■ Not fully hearing information because of our

inability to juggle multiple facts during a crisis.

■ Not remembering as much of the information as

we normally could.

■ Misinterpreting confusing action messages.

To cope, many of us may not attempt a logical and

reasoned approach to decision making. Instead, we

may rely on habits and long-held practices. We might

follow bad examples set by others.

Use simple messages.

We hold on to current beliefs.

5,6

Crisis communication sometimes requires asking

people to do something that seems counterintuitive,

such as evacuating even when the weather

looks calm.

Changing our beliefs during a crisis or emergency

may be difficult. Beliefs are often held very strongly

and not easily altered. We tend not to seek evidence

that contradicts beliefs we already hold.

We also tend to exploit any conflicting or

unclear messages about a subject by interpreting

it as consistent with existing beliefs. For example,

we might tell ourselves, “I believe that my house is a

safe place.” Before an impending hurricane, however,

experts may recommend that we evacuate from

an insecure location and take shelter in a building

that is stronger and safer. Although the action

advised is actually for us to evacuate our house to

seek a safer shelter, we can easily misinterpret the

recommendation to match our current beliefs. We

might say, “My home is strong and safe. I’ve always

been secure in my home. When we left last time, the

hurricane went north of us anyway. I’ll just stay here.”

Faced with new risks in an emergency, we may

have to rely on experts with whom we have little

or no experience. Often, reputable experts disagree

regarding the level of threat, risks, and appropriate

advice. The tendency of experts to offer opposing

views leaves many of us with increased uncertainty

and fear. We may be more likely to take advice from a

trusted source with which we are familiar, even if this

source does not have emergency-related expertise

and provides inaccurate information.

Messages should come from a credible source.

4 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

We look for additional information and opinions.

7, 8

We remember what we see and tend to believe what

we’ve experienced. During crises, we want messages

confirmed before taking action. You may find that

you or other individuals are likely to do the following:

■ Change television channels to see if the same

warning is being repeated elsewhere.

■ Try to call friends and family to see if others have

heard the same messages.

■ Turn to a known and credible local leader for

advice.

■ Check multiple social media channels to see what

our contacts are saying.

In cases where evacuation is recommended, we tend

to watch to see if our neighbors are evacuating before

we make our decision. This confirmation first—before

we take action—is very common in a crisis.

Use consistent messages.

We believe the first message.

9

During a crisis, the speed of a response can be an

important factor in reducing harm. In the absence

of information, we may begin to speculate and fill

in the blanks. This often results in rumors. The first

message to reach us may be the accepted message,

even though more accurate information may follow.

When new, perhaps more complete information

becomes available, we compare it to the first

messages we heard.

Because of the ways we process information while

under stress, when communicating with someone

facing a crisis or disaster, messages should be

simple, credible, and consistent. Speed is also very

important when communicating in an emergency. An

effective message must do the following:

■ Be repeated.

■ Come from multiple credible sources.

■ Be specific to the emergency being experienced.

■ Offer a positive course of action that can

be executed.

Release accurate messages as soon as possible.

5 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Mental States in a Crisis

During a disaster, people may experience a wide

range of emotions. Psychological barriers can

interfere with cooperation and response from the

public. Crisis communicators should expect certain

patterns, as described below, and understand that

these patterns affect communication.

There are a number of psychological barriers

that could interfere with cooperation and response

from the public. A communicator can mitigate

many of the following reactions by acknowledging

these feelings in words, expressing empathy, and

being honest.

Uncertainty

Unfortunately, there are more questions than

answers during a crisis, especially in the beginning.

At that time, the full magnitude of the crisis, the

cause of the disaster, and the actions that people

can take to protect themselves may be unclear.

This uncertainty will challenge even the greatest

communicator.

To reduce their anxiety, people seek out

information to determine their options and confirm

or disconfirm their beliefs. They may choose a

familiar source of information over a less familiar

source, regardless of the accuracy of the provided

information.

7

They may discount information that is

distressing or overwhelming.

Many communicators and leaders have been

taught to sound confident even when they are

uncertain. While this may inspire trust, there is a

potential for overconfidence, which can backfire. It is

important to remember that an over-reassured public

isn’t the goal. You want people to be concerned,

remain vigilant, and take all the right precautions.

Acknowledge uncertainty. Acknowledge and

express empathy for your audience’s uncertainty

and share with them the process you are using to

get more information about the evolving situation.

This will help people to manage their anxiety. Use

statements such as, “I can’t tell you today what’s

causing people in our town to die so suddenly, but I

can tell you what we’re doing to find out. Here’s the

first step…”

Tell them

■ What you know.

■ What you don’t know.

■ What process you are using to get answers.

Although we can hope for certain outcomes, we

often cannot promise that they will occur. Instead of

offering a promise outside of your absolute control,

such as “we’re going to catch the evil people who

did this,” promise something you can be sure that

response officials will do, such as “we’re going to

throw everything we have at catching the bad guys,

or stopping the spread of disease, or preventing

further flood damage.”

Former New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani

cautioned, “Promise only when you’re positive. This

rule sounds so obvious that I wouldn’t mention it

unless I saw leaders break it on a regular basis.”

10

A

danger early in a crisis, especially if you’re responsible

for fixing the problem, is to promise an outcome

outside your control. Never make a promise, no

matter how heartfelt, unless it’s in your absolute

power to deliver.

6 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Fear, Anxiety, and Dread

In a crisis, people in your community may feel

fear, anxiety, confusion, and intense dread. As

communicators, our job is not to make these feelings

go away. Instead, you could acknowledge them in a

statement of empathy. You can use a statement like,

“we’ve never faced anything like this before in our

community and it can be frightening.”

Fear is an important psychological consideration

in the response to a threat. Bear in mind the

following aspects of fear:

■ In some cases, a perceived threat can motivate and

help people take desired actions.

■ In other cases, fear of the unknown or fear of

uncertainty may be the most debilitating of the

psychological responses to disasters and prevent

people from taking action.

■ When people are afraid, and do not have adequate

information, they may react in inappropriate ways

to avoid the threat.

Communicators can help by portraying an accurate

assessment of the level of danger and providing action

messages so that affected people do not feel helpless.

Hopelessness and Helplessness

Avoiding hopelessness and helplessness is a

vital communication objective during a crisis.

Hopelessness is the feeling that nothing can be

done by anyone to make the situation better. People

may accept that a threat is real, but that threat may

loom so large that they feel the situation is hopeless.

Helplessness is the feeling that people have that

they, themselves, have no power to improve their

situation or protect themselves. If a person feels

helpless to protect him- or herself, he or she may

withdraw mentally or physically.

According to psychological research, if

community members let their feelings of fear,

anxiety, confusion, and dread grow unchecked

during a crisis, they will most likely begin to feel

hopeless or helpless.

11

If this happens, community

members will be less motivated and less able to take

actions that could help themselves.

Instead of trying to eliminate a community’s

emotional responses to the crisis, help community

members manage their negative feelings by

setting them on a course of action. Taking an

action during a crisis can help to restore a sense of

control and overcome feelings of hopelessness and

helplessness.

11

Helping the public feel empowered

and in control of at least some parts of their lives may

also reduce fear.

As much as possible, advise people to take

actions that are constructive and directly relate to the

crisis they’re facing. These actions may be symbolic,

such as putting up a flag or preparatory, such as

donating blood or creating a family check-in plan.

7 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Denial

Denial refers to the act of refusing to acknowledge

either imminent harm or harm that has already

occurred. Denial occurs for a variety of reasons:

■ People may not have received enough information

to recognize the threat.

■ They may assume the situation is not as bad as

it really is because they have not heard the most

recent warnings, didn’t understand what they were

told, or only heard part of a message.

■ They may have received messages about a threat

but not received action messages on how people

should respond to the threat.

■ They may receive and understand the message,

but behave as if the danger is not as great

as they are being told. For example, people

may get tired of evacuating for threats that

prove harmless, which can cause people to

deny the seriousness of future threats.

When people doubt a threat is real, they may seek

further confirmation. With some communities, this

confirmation may involve additional factors, such as

the following:

■ A need to consult community leaders or experts

for specific opinions.

■ The desire to first know how others are responding.

■ The possibility that the warning message of the

threat is so far outside the person’s experience that

he or she simply can’t make sense of it—or just

chooses to ignore it.

Denial can, at least in part, be prevented or

addressed with clear, consistent communication

from a trusted source. If your audience receives and

understands a consistent message from multiple

trusted sources, they will be more likely to believe

that message and act on it.

What about Panic?

Contrary to what you may see in the movies, people

seldom act completely irrationally during a crisis.

12

During an emergency, people absorb and act on

information differently from nonemergency situations.

This is due, in part, to the fight-or-flight mechanism.

The natural drive to take some action in response

to a threat is sometime described as the fight-or-

flight response. Emergencies create threats to our

health and safety that can create severe anxiety,

stress, and the need to do something. Adrenaline, a

primary stress hormone, is activated in threatening

situations. This hormone produces several responses,

including increased heart rate, narrowed blood

vessels, and expanded air passages. In general, these

responses enhance people’s physical capacity to

respond to a threatening situation. One response

is to flee the threat. If fleeing is not an option

or is exhausted as a strategy, a fight response is

activated.

13

You cannot predict whether someone will

choose fight-or-flight in a given situation.

These rational reactions to a crisis, particularly

when at the extreme ends of fight-or-flight, are

often described erroneously as “panic” by the media.

Response officials may be concerned that people

will collectively “panic” by disregarding official

instructions and creating chaos, particularly in public

places. This is also unlikely to occur.

If response officials describe survival behaviors as

“panic,” they will alienate their audience. Almost no

one believes he or she is panicking because people

understand the rational thought process behind

their actions, even if that rationality is hidden to

spectators. Instead, officials should acknowledge

people’s desire to take protective steps, redirect

them to actions they can take, and explain why the

unwanted behavior is potentially harmful to them or

the community. Officials can appeal to people’s sense

of community to help them resist unwanted actions

focused on individual protection.

In addition, a lack of information or conflicting

information from authorities is likely to create

heightened anxiety and emotional distress. If you start

hedging or hiding the bad news, you increase the risk

of a confused, angry, and uncooperative public.

8 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

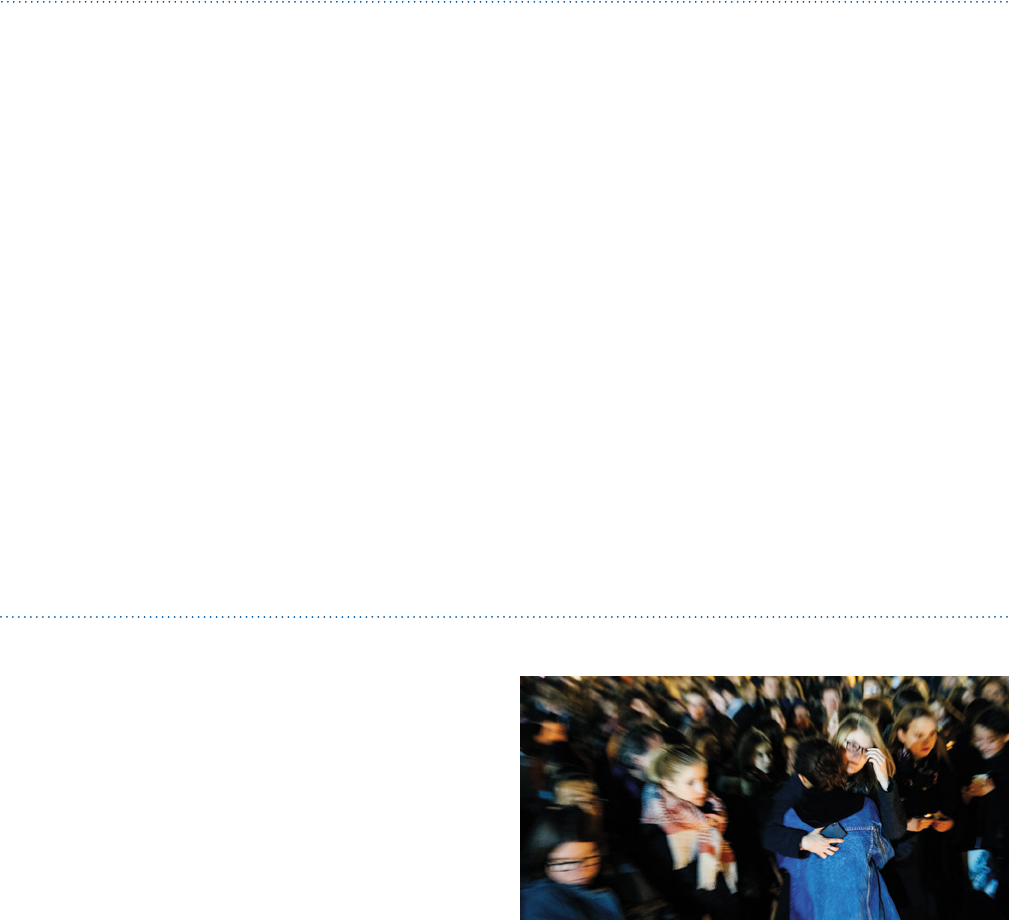

Media Coverage of Crisis and Potential Psychological Effects

As we will see later in this chapter, most of us tend to

have stronger psychological and emotional reactions

to a crisis if it’s manmade or imposed.

14

These types

of crises also tend to have increased media exposure.

The media will often show repeated negative images,

such as the following:

■ People who are dying or in distress.

■ People who lack food and water.

■ Animals that have been abandoned, hurt, or

covered in oil.

■ Landscapes, such as collapsed buildings, flooded

homes, or oil floating on top of water.

Those who are indirectly affected by the crisis

through media exposure may personalize the event

or see themselves as potential victims. For example,

on September 11, 2001, adults watched an average

of 8.1 hours of television coverage, and children

watched an average of 3.0 hours.

14

Several studies

show that the amount of time spent watching TV

coverage and the graphic content of the attacks

on September 11 was associated with increased

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and clinical

depression symptoms.

15,16,17

This was even true

for those far away from disaster sites. In addition,

those who were directly affected by the attacks and

watched more television coverage had higher rates

of PTSD symptoms and depression than those who

did not.

As you are planning your communication

strategy, remember that even those people not

directly affected by an emergency may have

substantial psychological effects. Communication

targeted at them will also need to use sound crisis

and emergency risk communication principles.

Behaviors in a Crisis

Proper crisis communication can address a variety of

potentially harmful behaviors during a crisis. Although

it may be difficult to measure the impact, using good

communication to persuade people to avoid negative

behaviors during a crisis will save lives, prevent

injuries, and lessen the misery people experience.

Some of these negative behaviors are listed here, with

advice on communication strategies to address them.

Seeking Special Treatment

Some people will attempt to bypass official channels

to get special treatment or access to what they want

during a crisis. For instance, in Richard Preston’s book

Demon in the Freezer, an account of the eradication

of smallpox, neighbors and friends approached the

wife of a prominent government smallpox researcher

asking for help to obtain smallpox vaccine in case

of a bioterrorist attack with smallpox.

18

The vaccine

9 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

was not available for these people through official

channels, so they reached out to someone with

influence, who they thought could assist them.

This behavior may result from the following:

■ A person’s sense of privilege.

■ A belief that officials cannot guarantee the

person’s well-being.

■ An inflated need to be in control.

■ A lack of awareness of available resources.

Whatever the cause, seeking special treatment

can be damaging to the harmony and recovery of

the community. If there is a perception that favored

people get special help, it invites anger among

community members and chaos when resources are

made available.

Some supplies or treatments may first be

given to priority groups who are either especially

vulnerable to the disaster, such as children and

elderly people, or whose safety is critical to an

effective response, such as healthcare workers.

The term “priority groups” may confuse some people,

who may be unclear about what criteria are used to

define priority and may assume they are important

enough to be in a priority group. To avoid this,

communicators can discuss those groups who have

the greatest need for treatment without referring to

them as “priority groups.”

Good communication can reduce some of these

reactions. The more honest and open government

officials are about resources, the better odds officials

have of reducing the urge among people in the

community to seek special treatment. The following

communication strategies can help communicators

persuade the public to avoid seeking special treatment:

■ Explain what resources are available.

■ Explain why some resources are not available.

■ Explain that limited supplies are being used for

people with the greatest need.

■ Explain who the people are with the greatest need.

■ Describe reasonable actions that people can take, so

that they do not focus on things they cannot have.

■ Keep open records of who receives what and when.

Remember, both people directly affected by the

crisis and those who anticipate being affected by

the crisis need enough information to help them

manage anxiety and avoid behaviors that may divide

the community.

Negative Vicarious Rehearsal

In an emergency, many communication and

response activities are focused on audiences who

were directly affected, such as survivors, people

who were exposed, and people who had the

potential to be exposed. However, these targeted

messages will also reach people who do not need

to take immediate action. Some of these unaffected

observers may mentally rehearse the crisis as if they

are experiencing it and practice the courses of action

presented to them.

In many cases, this mental rehearsal can help to

prepare people for the actions they should take in an

emergency. This may reduce anxiety and uncertainty.

As a communicator, you may encourage this type

of mental rehearsal by asking an audience not yet

affected by an emergency to create an emergency

plan of action according to your recommendations.

Other times, spectators farther away from the

emergency may be much more critical about the

value of your recommendations because they have

more time to decide their chosen course of action.

In some cases, they may reject the proposed course

of action and choose another. If a person rejects an

action, it may be harder for that person to take that

action in the future. For example, if people hear a

story about a search and rescue effort for someone

lost in the wilderness they may mentally rehearse

how they would act in a similar situation. If they plan

out creating an elaborate shelter, starting a fire and

finding food, instead of finding a simple shelter

and water and waiting for rescue, then those are

the actions they might choose to take in the event

that they do find themselves lost in the wilderness.

This would decrease their survival chances because

they would waste their energy and resources on less

important actions.

People practicing negative vicarious rehearsal

might decide that they are at the same risk as

those directly affected by the emergency and need

the recommended remedy, such as a visit to an

emergency room or a vaccination. These people,

sometimes referred to as the “worried well,” may

heavily tax response resources by requesting medical

treatment they do not need. For example, during

10 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and radiation disaster

in Japan, people who lived on the west coast of the

United States and Canada began to worry about

radiation exposure coming across the ocean. Because

people very close to the danger in Japan had been

advised to take potassium iodide (KI) to mitigate

effects of radiation, some people in North America

thought they should take KI too. In fact, when

unneeded, KI has dangerous side effects and should

not be used.

Communicators can help to address the effects

of negative vicarious rehearsal by creating simple

action steps that can be taken by the people not

directly affected by an emergency. Simple actions

in an emergency will give people a better sense of

control and will help to motivate them to stay tuned

to your messages. During the Japan emergency,

communicators related to people on the West Coast

what they could do to help people in Japan; what

they could do to learn more about actual levels of

radiation reaching the United States; and directed

them to fact sheets about when KI was and was

not necessary. “Let your friends know KI can be

dangerous when not needed” became a new action

people could take.

When communicators create messages, they

are likely to segment their target audience into

groups who need to take different types of action.

The challenge is to convince people unaffected

by the emergency to delay taking the same action

recommended to people directly affected unless

their circumstances change. Create alternative action

messages for those people who are vicariously

experiencing the threat, but who should not take

the action currently being recommended to those

directly affected.

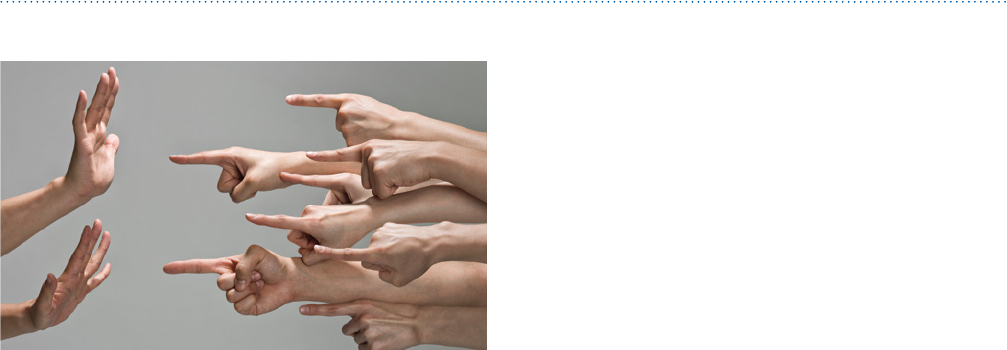

Stigmatization

Stigmatization can affect a product, an animal, a

place, and an identifiable group of people. It occurs

when the risk is not present in the stigmatized

minority group but people associate the risk with

that group. Stigmatization is especially common in

disease pandemics.

If a population becomes stigmatized, members of

this group may experience emotional pain from the

stress and anxiety of social avoidance and rejection.

Stigmatized people may be denied access to health

care, education, housing, and employment. They may

even be victims of physical violence.

Crisis communicators must be aware of the

possibility that, although unintentional and

unwarranted, segments of their community could

be shunned because some perceive them as being

identified with the problem. This could have both

economic and psychological impact on the well-

being of members of the community and should

be challenged immediately. This stigmatization can

occur without any scientific basis. It can come not

only from individuals, but entire nations. During the

first avian influenza outbreak in Hong Kong during

1997–98 and during the first West Nile virus outbreak

in New York City in 1999, the policies of some other

nations banned the movement of people or animals,

despite the absence of clear science calling for those

measures.

Communication professionals must help to

counter potential stigmatization during a disaster.

You should be cautious about images you share

repeatedly and understand that constant portrayal

of a segment of the population in images may

contribute to stigmatization. For instance, if the

images accompanying a news story about a disaster

consistently show members of a particular ethnic

group, this may reinforce the idea that the disaster

is associated with members of that ethnic group. If

stigmatizing statements or behaviors appear, public

health officials must offset this with accurate risk

information that people can understand, and speak

out against the negative behavior.

It is important to remember that even if

stigmatization decreases through the beginning

of the crisis lifecycle, the stigma may return in the

resolution phase. As misery and anger turns to fault-

finding and blame, the group of people perceived to

be responsible for the disaster could be stigmatized

once again. Keep this in mind when creating your

communication strategy.

11 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Harmful Actions Brought About by

Crisis-Related Psychological Issues

Without communication from a source that is

trusted by the audience to lessen the psychological

impact, negative emotions may lead to harmful

individual or group behaviors. These behaviors may

affect the public’s safety by slowing the speed,

quality, and appropriateness of a crisis response and

recovery. Crisis-related psychological issues may lead

to further loss of life, health, safety, and property.

Harmful actions may include the following:

■ Misallocating treatments based on demand rather

than medical need.

■ Accusations of providing preferential treatment

and bias in providing aid.

■ Creating and spreading damaging rumors and

hoaxes directed at people or products.

■ Offering unfounded predictions of greater

devastation.

■ Encouraging an unfair distrust of response

organizations.

■ Attempting bribery for scarce or rationed

treatments and resources.

■ Depending on special relationships to ensure

considerations based on desire, not need.

People in a crisis tend to have more unexplained

physical symptoms. Stress caused by a crisis situation

will give some people physical symptoms, such

as headaches, muscle aches, stomach upsets, and

low-grade fevers.

19

In emergencies involving disease

outbreaks, these symptoms could confound the

effort to identify those people who need immediate

care versus those who need only limited treatment or

limited access to medication.

Positive Responses following a Crisis

Crises do not only create negative emotions and

behaviors. Positive responses might include coping,

altruism, relief, and elation at surviving the disaster.

Feelings of excitement, greater self-worth, strength,

and growth may come from the experience. Often

a crisis results in changes in the way the future is

viewed, including a new understanding of risks and

new ways to manage them.

How quickly the crisis is resolved and the degree

to which resources are made available will make a

difference. Many of these positive feelings associated

with a successful crisis outcome depend on

effective management and communication. Positive

responses may include the following:

■ Relief and elation.

■ Sense of strength and empowerment.

■ New understanding of risk and risk management.

■ New resources and skills for risk management.

■ Renewed sense of community.

■ Opportunities for growth and renewal.

12 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Risk Perception

20,21

Not all risks are perceived equally by an audience.

Risk perception can be thought of as a combination

of hazard, the technical or scientific measure of a

risk, and outrage, the emotions that the risk evokes.

Risk perception is not about numbers alone.

Don’t dismiss outrage. The mistake some

officials make is to measure the magnitude of the

crisis only based on how many people are physically

hurt or how much property is destroyed. Remember

that we must also measure the catastrophe

in another way: the level of emotional trauma

associated with it.

As a communicator, expect greater public outrage

and more demands for information if what causes the

risk is manmade and, especially, if it’s intentional and

targeted. Unfairly distributed, unfamiliar, catastrophic,

and immoral events create long-lasting mental health

effects that lead to anger, frustration, helplessness,

fear, and a desire for revenge. A wide body of research

exists on issues surrounding risk communication,

but the following explains how some risks are more

accepted than others:

■ Voluntary versus involuntary: Voluntary

risks are more readily accepted than imposed

risks. Example: elective knee surgery v. emergency

appendectomy.

■ Personally controlled versus controlled by

others: Risks controlled by the individual or

community are more readily accepted than risks

outside the individual’s or community’s control.

Example: choosing to house a nuclear reactor in the

community v. having a nuclear reactor built in your

community against your wishes.

■ Familiar versus exotic: Familiar risks are more

readily accepted than unfamiliar risks. Example:

seasonal influenza v. a new respiratory illness.

■ Natural origin versus manmade: Risks

generated by nature are better tolerated than risks

generated by man or institution. Example: a natural

disaster v. an oil spill.

■ Reversible versus permanent: Reversible

risk is better tolerated than risk perceived to be

irreversible. Example: having a broken leg v. having

an amputated leg.

■ Endemic versus epidemic: Illnesses, injuries, and

deaths spread over time at a predictable rate are

better tolerated than illnesses, injuries, and deaths

grouped by time and location. Example: seasonal

influenza v. pertussis (whooping cough) outbreak.

■ Fairly distributed versus unfairly distributed:

Risks that do not appear to single out a group,

population, or individual are better tolerated than

risks that are perceived to be targeted. Example:

water pollution that is citywide v. water pollution in a

minority neighborhood.

■ Generated by trusted institution versus

mistrusted institution: Risks generated by a

trusted institution are better tolerated than risks

that are generated by a mistrusted institution.

Example: air pollution by coal plant that is a longtime

area employer v. air pollution by new and unknown

company.

■ Adults versus children: Risks that affect adults

are better tolerated than risks that affect children.

Example: lead paint in an office building v. lead paint

in a school.

■ Understood benefit versus questionable

benefit: Risks with well-understood potential

benefit and the reduction of well-understood

harm are better tolerated than risks with little or no

perceived benefit or reduction of harm. Example:

chemotherapy for cancer is a risk with a well-

understood benefit.

■ Statistical versus anecdotal: Statistical risks

for populations are better tolerated than risks

represented by individuals. Example: an anecdote

shared with a person or community, even if it is

explained to be a “one in a million” event, can be

more damaging than a statistical risk of one in 10,000

presented as a number.

13 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Addressing Psychology in

the CERC Rhythm

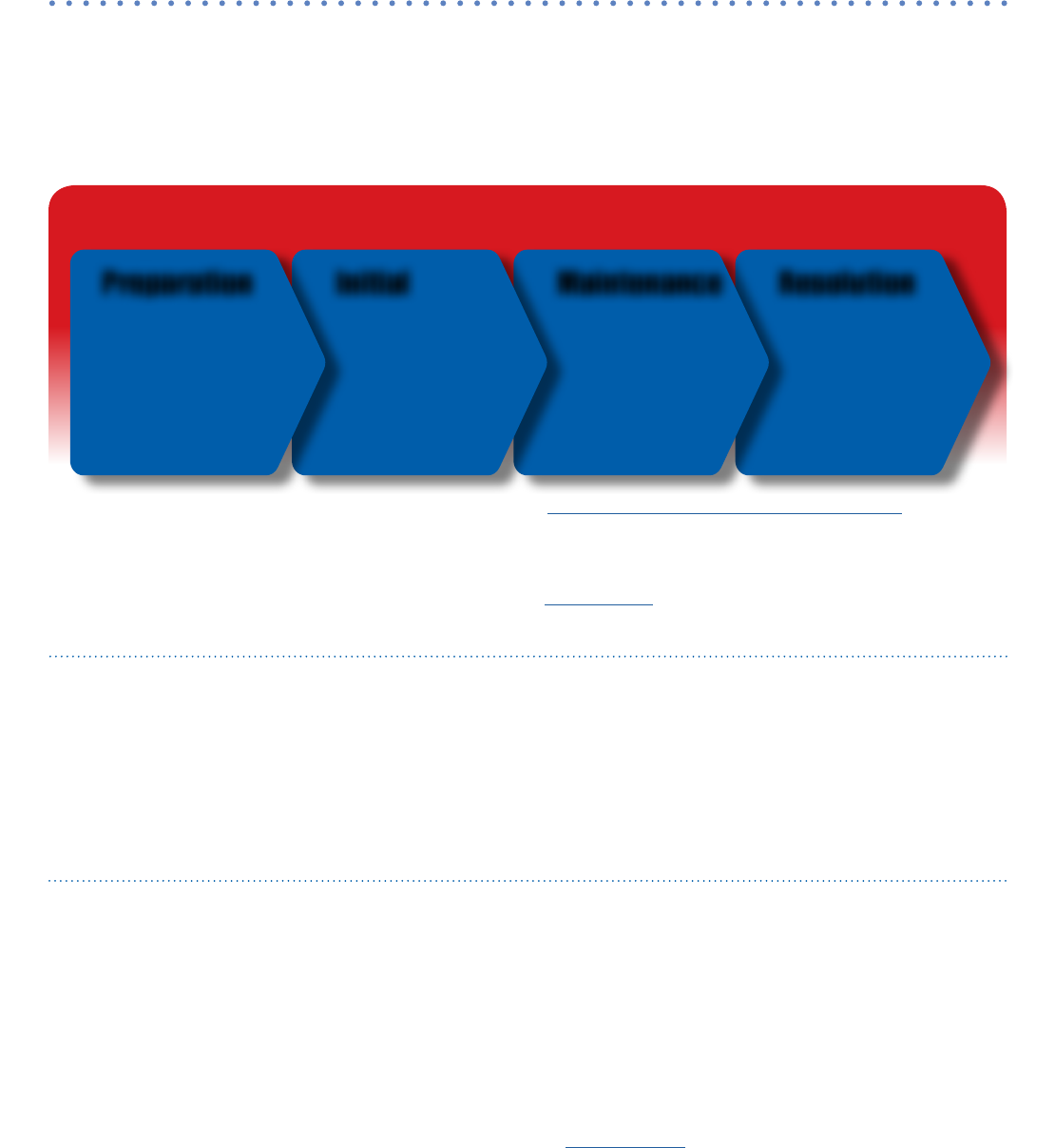

The CERC Rhythm graphic shows the four phases of a crisis. Accessible explanation of figure in Appendix, page 16.

In addition to the principles of risk communication

described, such as expressing empathy and being

respectful, it’s important to consider how the situation

changes during each phase of a crisis and how risk

communication can be applied during each phase.

Although these phases were discussed in our

introduction, it’s helpful to have a more in-depth

picture of each category.

Preparation

Important information and assumptions are set

during the pre-crisis stage even before a crisis occurs.

Develop plans and establish open communication

during this phase.

Provide an open and honest flow of

information to the public: Generally, more harm is

done by officials trying to avoid panic by withholding

information or over-reassuring the public, than is

done by the public acting irrationally in a crisis. Pre-

crisis planning should assume that you will establish

an open and honest flow of information.

Initial

During this stage of acute danger, the priority

for all is basic safety and survival. Most people

respond appropriately to protect their lives and

the lives of others.

22

To reduce the threat, they

create spontaneous efforts to cooperate with

others. However, some may behave in disorganized

ways and may not respond as expected. The more

stress felt in a crisis, the greater the impact on the

individual. Important causes of stress include the

following:

■ Threat to life and encounters with death.

■ Feelings of powerlessness and helplessness.

■ Personal loss and dislocation, such as being

separated from loved ones or home.

■ Feelings of being responsible, such as telling

oneself “I should be doing more.”

■ Feelings of facing an inescapable threat.

■ Feelings of facing malevolence from others, such

as deliberate efforts that cause harm.

During the initial phase, the following CERC concepts

are important. These concepts are explained further

in spokesperson.

■ Don’t over-reassure.

■ Acknowledge uncertainty.

■ Emphasize that a process is in place to

learn more.

■ Be consistent in providing messages.

Engage Community • Empower Decision-Making • Evaluate

The CERC Rhythm

Preparation ResolutionMaintenanceInitial

■ Draft and test

messages

■ Developpartnerships

■ Create plans

■ Determine approval

process

■ Express empathy

■ Explain risks

■ Promote action

■ Describe response

efforts

■ Explain ongoing risks

■ Segment audiences

■ Provide background

information

■ Address rumors

■ Motivate vigilance

■ Discuss lessons

learned

■ Revise plan

14 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Put the good news in secondary clauses

For example, “it’s too soon to say we’re out of the woods, even though we haven’t seen a new anthrax case

in X days.” The main clause indicates that you are taking the situation seriously and that you are responding

aggressively. The secondary clause includes the reassuring information without over-reassuring.

Maintenance

During this phase, the crisis magnitude, the concept

of personal risk, and the initial steps toward recovery

and resolution are in motion. Emotional reactions vary

and will depend on perceptions about the risk and

the stresses people experienced or anticipated. At first

people may appear to be elated, despite surrounding

destruction or death, because they are relieved they

survived. However, as the maintenance phase evolves,

people may experience varied emotional states,

including numbness, denial, flashbacks, grief, anger,

despair, guilt, and hopelessness.

The longer the maintenance phase lasts, the

greater these reactions. Once basic survival needs are

met, other needs for emotional balance and self-

control emerge. People often become frustrated and

let down if they are unable to return to more normal

conditions. Early selfless responses to the emergency

may fall away and be replaced by negative emotions

and blame.

The following CERC principles apply to the

maintenance phase and are further explained in the

chapter on spokesperson:

■ Acknowledge fears.

■ Express wishes.

■ Give people things to do.

■ Acknowledge shared misery.

■ Give anticipatory guidance (foreshadow).

Resolution

When the emergency is no longer on the front

page, those who have been most severely affected

will continue to have significant emotional needs.

Emotional symptoms may present as physical health

symptoms such as sleep disturbance, indigestion, or

fatigue. They may cause difficulties with interpersonal

relationships at home and work. At this point,

organized external support often starts to erode

and the realities of loss, bureaucratic controls, and

permanent life changes come crashing down.

To maintain trust and credibility during the

resolution phase, keep the expressed commitments

from the initial phase. Failures or mistakes should be

acknowledged and carefully explained.

15 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

References

1. Seeger MW, Sellnow TL, Ulmer RR. Communication and organizational crisis. Westport (CT): Praeger; 2003.

2. Covello VT, Peters RG, Wojtecki JG, Hyde RC. Risk communication, the West Nile virus epidemic, and

bioterrorism: responding to the communication challenges posed by the intentional or unintentional

release of a pathogen in an urban setting. J Urban Health 2001;78(2):382–391.

3. Glik DC. Risk communication for public health emergencies. Annu Rev Public Health 2007;28: 33–54.

4. Hill D. Why they buy. Across the Board 2003;40(6):27–33.

5. Andreasen AR. Marketing social change: changing behavior to promote health, social development, and

the environment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers;1995.

6. Brehm SS, Kassin S, Fein S. Social psychology. 6th ed.Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.;2005.

7. Brashers DE. Communication and uncertainty management. J Commun 2001;51(3):477–497.

8. Sellnow TL, Ulmer RR, Seeger MW, Littlefield RS. Effective risk communication: A message-centered

approach. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC;2009.

9. Solso RL. Cognitive psychology. 6th ed. Boston:Allyn and Bacon;2001.

10. Giuliani, R. Leadership. New York: Miramax; 2005. p. 164–165.

11. Benight CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-

efficacy. Behaviour research and therapy, 42(10), 1129–1148;2004.

12. Clarke, L. The problem of panic in disaster response. [online]. 2003. [cited 2019 Feb]. Available from URL:

http://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/our-work/events/2003_public-as-asset/Transcripts/index.html#clarke.

13. Sellnow TL, Seeger MW. Theorizing crisis communication. Malden (MA): Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. p. 7.

14. Novac A. Traumatic stress and human behavior. Psychiatric Times [online] 2001 Apr [cited 2019 Feb]; 18(4).

Available from URL: http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/dissociative-identity-disorder/traumatic-stress-and-

human-behavior.

15. Ahern J, Galea S, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, et al. (2002). Television images and psychological symptoms after

the September 11 terrorist attacks. Psychiatry, 65(12), 289–300;2002.

16. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Collins RL, Marshall GN, Elliott MN, Berry SH. A national survey of stress

reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New Engl J Med, 345(20), 1507–1512;2001.

17. Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, Jordan BK, Rourke KM, Wilson D, Kulka RA. Psychological reactions to

terrorist attacks: findings from the national study of americans’ reactions to September 11. J Am Med,

288(5), 581–588;2002.

18. Preston R. The demon in the freezer. New York: Random House; 2003.

19. Stuart JA, Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Norwood AE, Murray K. Belief in exposure to terrorist agents: reported

exposure to nerve or mustard gas by Gulf War veterans. Journal of nervous and mental disease, 191(7),

431–436; 2003.

20. Cohn V. Reporting on risk: getting it right in an age of risk. Washington (DC): The Media Institute; 1990.

21. Covello V. Communicating Radiation Risks. Crisis communications for emergency responders. EPA

Document 402-F-07-008 [online]. 2007. [cited 2019 Feb]. Available from URL: http://tinyurl.com/6lva2sk

22. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for PTSD. Phases of traumatic stress reactions in a

disaster. Impact phase [online]. 2018 Jan. [cited 2019 Feb]. Available from URL: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/

professional/treat/type/index.asp.

16 CERC: Psychology of a Crisis

Resources

■ American Psychological Association. The effects of trauma do not have to last a lifetime [online]. 2004 Jan 16.

[cited 2019 Feb]. Available from URL: http://www.apa.org/research/action/ptsd.aspx.

■ DeWolfe, DJ. Mental health response to mass violence and terrorism: a field guide. DHHS Pub. SMA 4025.

Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [online]. 2005. [cited 2019 Feb].

Available from URL: https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Mental-Health-Response-to-Mass-Violence-and-

Terrorism-A-Field-Guide/SMA05-4025

■ DiGiovanni C Jr. Domestic terrorism with chemical or biological agents: psychiatric aspects. Am J Psychiatry

1999 Oct;156(10):1500–5.

■ Everly GS Jr, Mitchell JT. America under attack: the “10 commandments” of responding to mass terrorist

attacks. Int J Emerg Ment Health 2001 Summer;3(3):133–5.

■ Krug EG, Kresnow M, Peddicord JP, Dahlberg LL, Powell KE, Crosby AE, et al. Suicide after natural disasters. N

Engl J Med 1998 Feb 5;338(6), 373–378.

■ Reynolds BJ. When the facts are just not enough: credibly communicating about risk is riskier when emotions

run high and time is short. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2011 Jul 15;254(2):206–14.

■ Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Collins RL, Marshall GN, Elliott MN, et al. A national survey of stress reactions

after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med 2001;345(20), 1507–1512.

■ Sandman, Peter M. The risk communication website. Risk = hazard + outrage [online]. 2004 [cited 2019 Feb].

Available from URL: http://www.psandman.com/index.htm.

■ Tinker, Tim L, and Elaine Vaughan. Risk and crisis communications:best practices for government agencies

and non-profit organizations. McLean, Va: Booz, Allen, Hamilton, 2010. Print.

■ U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for PTSD. Psychological first aid: field operations guide

[online]. 2006. [cited 2019 Feb]. Available from URL: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/type/psych_

firstaid_manual.asp.

■ U.S. National Library of Medicine. Current bibliographies in medicine 2000–2007. Health risk communication

[online]. 2000 Oct. [cited 2019 Feb]. Available from URL: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/archive/20061214/pubs/

cbm/health_risk_communication.html

Appendix: Accessible Explanation of Figures

The CERC Rhythm (page 13): Crisis communication

needs and activities evolve through four phases

in every emergency. The first phase is preparation.

During preparation communicators should

draft and test messages, develop partnerships,

create communication plans, and determine the

approval process for sending out information in an

emergency. The second phase is the initial phase.

During the initial phase of a crisis communicators

should express empathy, explain risks, promote

action, and describe response efforts. During the

third phase, maintenance, communicators need

to explain ongoing risks and will have more time

to segment audiences, providing background

information, and addressing rumors. The final phase,

resolution, requires communicators to motivate the

public to stay vigilant and communicators should

discuss lessons learned and revise communication

plans for future emergencies. Throughout all phases,

CERC encourages communicators to engage

communities, empower community members to

make decisions that impact their health, and evaluate

communication efforts.